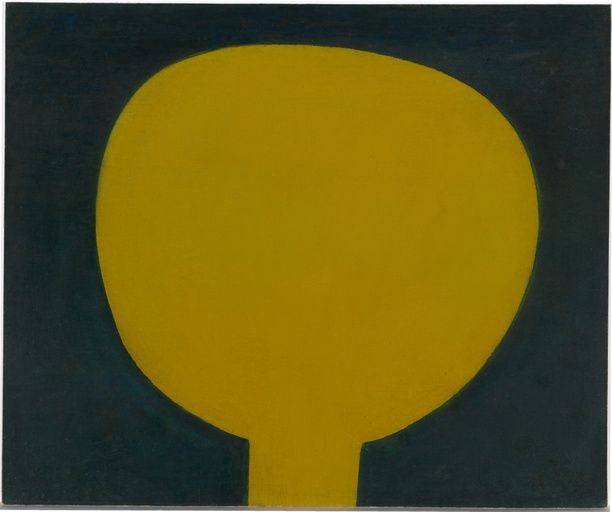

Boy and the moon, c. 1940

Boy and the moon [Moonboy] circa 1939-40, oil on canvas, mounted on composition board, 73.3 x 88.2 cm, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Purchased 1976, NGA 76.560, © Sidney Nolan Trust

Natalie Wilson is a Curator at Australian & Pacific Art, Art Gallery of New South Wales.

“It has been likened to a lavatory seat; to the rising plume of debris thrust into the atmosphere following an atomic blast; the tree of life; and the emblematic Rising Sun Flag used by feudal warlords in Japan during the Edo period. Readings of this deceptively unassuming image are numerous.

While working as an illustrator and sign-writer in the mid-1930s, the young Sidney Nolan absorbed the imagery and words of the world’s greats, garnered through his untutored study of art history and literature in the collections of the State Library of Victoria. Consequently, there is conjecture about a probable source of inspiration for this enigmatic work: the poetic works of Rainer Maria Rilke or Arthur Rimbaud, or from artists such as William Blake, Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso or Henri Matisse.

Literally, the painting is a mass of mustard-yellow — ovoid in form with a stalk-like protrusion at its base — silhouetted against a ground of blue-black. The golden orb fills almost three-quarters of the picture plane. This distinctive head/tree shape is one that Nolan reinvented continually over his long career: as the ‘original’ painting Boy and the moon (later named Moonboy by Nolan’s patron, lover and muse Sunday Reed), first exhibited at the 2nd Annual Contemporary Art Society exhibition in 1940; in the lyrical series of ‘figure and tree’ works of 1941, including Woman and tree (or Garden of Eden) in the collection of the Heide Museum of Modern Art; and through the ‘Moonboy mural’, writ large on the roof of the Reed’s cottage at Heide during World War II, subsequently removed at the insistence of air-force intelligence, fearing it a target for Japanese bombers.

Two decades later, in 1962, Nolan would repeat this grand gesture, reborn on a momentous scale, when he designed the sets and costumes for Kenneth MacMillan’s production of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring at London’s Royal Opera House. A spectacular feature of the ballet was Nolan’s design for the backcloth to Act 2: The sacrifice. Rising from the stage on a background of deep indigo blue blazed a shimmering sphere — shifting hue from whitish-silver to ox-blood red — against which the dancers soared, the totemic form of Moonboy presiding over the final climax of the ballet.

Nolan himself claimed that this semi-abstract shape had no emotional content, that the idea came simply from observing his friend’s head one night while sitting on a bench in Melbourne’s seaside suburb of St Kilda, as a full moon rose above the horizon (the work is also known as Portrait of John Sinclair at St Kilda).

Yet I can’t help but be reminded of William Blake’s frontispiece to his illuminated book, The Song of Los, in which a glowing sphere emanates from a darkened space. Created in 1795, during the period following the American War of Independence and the outbreak of revolutionary activity in London, The Song of Los is one of a series of books known as the Continental Prophecies. In Blake’s invented mythology, Los represented imagination, his purpose to create his own system, distinct from all others. So too, in a time of global conflict and the conservative oppression of 1940s Australia, Nolan’s conception of Moonboy can be viewed as a defining moment, when the artist began to construct his own visual language, culminating in the idiosyncratic apparition of a cut-out black square infiltrating the Australian landscape: the mythological figure of the helmeted Ned Kelly that Nolan would make his own five years later.”