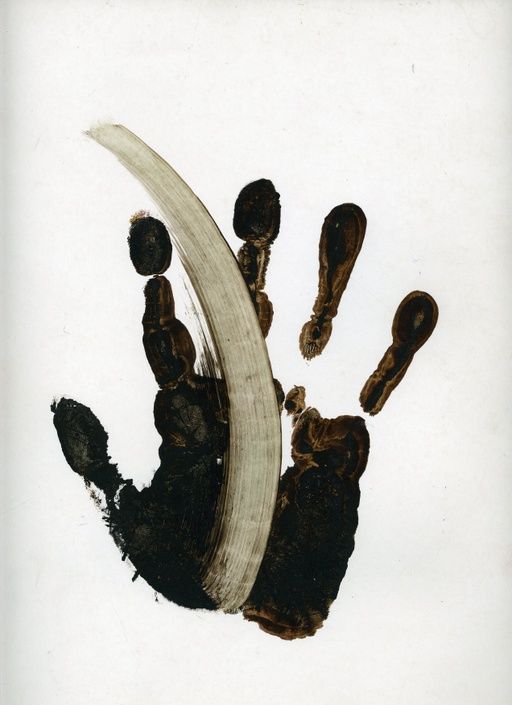

Study for Samson et Dalila, 1981

Sidney Nolan. Study for Samson et Dalila, 1981. Ink on card. Copyright Sidney Nolan Trust. 30.5cm x 24cm

Elijah Moshinsky (8 January 1946 – 14 January 2021)[1] was an Australian opera director, theatre director and television director who worked for the Royal Opera House, the Metropolitan Opera, the Royal National Theatre, and BBC Television, among other organisations.

Working with Sidney Nolan on the design of Samson et Dalila at Covent Garden, 1981

"I was invited by Sir John Tooley to direct a new production of Samson et Dalila by Saint-Saens to be conducted by Sir Colin Davis, with Jon Vickers and Shirley Verrett. Who did I think would be the appropriate designer for this project?

The opera was not highly regarded at the time and considered to be a sort of French orientalist perfumed affair and a piece of kitsch. I rather admired the opera and thought that it needed a visual presentation which took it out of ordinary stage design and into a realm of biblical symbolism. I immediately thought of Sidney Nolan whose paintings were inscribed into my Australian unconscious. John Tooley seemed excited by the idea and the next day I was told that he had spoken to Nolan who was fascinated by the prospect of designing an opera, and could I meet him at his apartment in Whitehall Court.

We met and it was an instant rapport. He did know the opera, he did not know the procedure to design a huge piece like this – I was to organise all that. But we talked about music. Music was of great importance to him. He was a connoisseur of nuance in performance. He told me that he chose to live in Whitehall Court because he said he could just walk across the bridge to the Festival Hall for concerts. Was Solti’s Beethoven better than Tennstedt’s? Did I not prefer Ashkenazy’s playing to Brendel’s? What about literature – Patrick White? Robert Frost or Auden?

This exciting talker, this man of enormous cultural sensibility who adored music, poetry and literature, totally enchanted me and a firm commitment was made to enter the project which would be performed about 7 months later.

At this point he then disappeared on a long journey to travel the silk route to Mongolia. Several months passed and Covent Garden began pressing me for designs to start work. There seemed no way to reach him but by some means John Tooley was able to get a message through to him and indeed received a phone call from Sidney which he imagined to be from a phone booth in the Gobi desert. Yes, Sidney was still on board with the venture and keen. He was about to return and had discovered exotic silk fabrics in China which he wanted to incorporate into the costumes.

A week later he was back. Covent Garden was about to go into its summer recess and we had to come up with a functioning design almost immediately.

We had decided that we wanted to create layers of imagery on gauze cloths, sometimes four deep, to provide a complete but shifting environment of colour and design for the stage action. A model of the Royal Opera House stage was built to a large scale into which he could experimentally hang his paintings. This was delivered to his studio and we began intensive work. We had to work intensely and quickly. I was to guide him step by step through the demands of the opera and build up the whole scheme of the production. This could only be done if we met every day and worked together as the model developed. He painted quickly and we would test the scale and value of each cloth in the model.

We would have lunch and discuss the plan for that day. I would read him the libretto, sometimes passages from the Bible, sometimes parts of Jung’s essays and sometimes Freud on Monotheism. We began by tackling the scene with the Hebrews at the beginning – how did this relate to the later scenes, moving to the world of Dalila? And he began to consider the scenes in terms of colour and texture. But we did not want scenery as conventionally understood. We did not want the kitsch of Hollywood Biblical epics. I wanted a stage in which the performers could populate the Nolan world.

‘What is that first scene about?’ Sidney kept enquiring. Not the action of the scene but its nub, its inner core. Eventually he forced me to find it. It was about God. The Israelites feeling lost and abandoned by Jehovah.

This idea absolutely hit him with force. He said ‘What if we do it from God’s point of view?’ He then painted, very quickly using vivid dyes a blue background and on it he put the imprint of his own hand painted black. The effect in performance would be that we saw the Israelites obscurely in white and blue sections of the stage picture, and the imprint of the black hand would act as a void through which we could see the disposed Hebrews clearly. This symbol, he explained to me, came to him from aboriginal rock paintings. It was, he said, the first expression of Man’s self awareness. For Nolan, it was a symbol of creativity in man, The Hand of God.

Standing next to him every day as we probed and invented the world of the opera, I was aware of a man who had a visionary grasp on his art, who could somehow actualise the mythic, the essential though behind ordinary reality. There was no stagey banality or indeed practicality in his work. It was there, to mine the inner core of some essential sense of man’s relationship to landscape, light, sexuality and tragedy.

When it came to devising the key image for the production, something that defined the core of the myth of Samson, Sidney came up with an enormously powerful image of the blind Samson, eyes streaming blood. It was about the tragedy of man himself. Samson / Oedipus, overwhelming in the theatre, red raw background surrounded the ghost shape of a face in agony with its eyes put out. Like the helmet of Ned Kelly, this Samson was an essential image of human suffering."